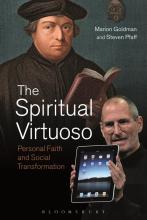

THE SPIRITUAL VIRTUOSO: PERSONAL FAITH AND SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION

Marion Goldman and Steven Pfaff*

Reviewed by Susan Pitchford

Every field of endeavor has its virtuosi: those rare ones whose mix of talent and drive cause them to excel. The field of spirituality is no different, as sociologist Max Weber noted a century ago. But while Weber gave most of his attention to spiritual virtuosi who’d withdrawn from the world, The Spiritual Virtuoso by Marion Goldman and Steven Pfaff shows that virtuosity can be socially transformative. Their focus is on the activist virtuoso, whose intense personal spirituality requires them to engage in public advocacy, especially in ways that democratize the pursuit of holiness.

In 21st century western culture, we’re accustomed to think of spirituality as primarily a private pursuit. What Goldman and Pfaff have accomplished is the placement of spiritual excellence in a social context, showing both the social supports necessary for virtuoso cultivation and how the religious creativity of virtuosi can bring about movements for change. Spiritual virtuosi have exceptional religious “talent,” but they also need material security (from personal wealth, patronage or institutional support) to nurture that talent.

To turn religious brilliance into a movement requires the right social conditions. Times of prosperity enable people to give their attention to matters beyond survival, for example. Further, even the most gifted spiritual pioneer needs people with whom they can sharpen their ideas; these “pivotal communities” play a key role in bringing those ideas, and the virtuosi themselves, to maturity. And however sublime the message, it won’t become a movement without the technology to communicate it.

Goldman and Pfaff provide three principal case studies that show how such factors enabled activist virtuosi to turn their private piety outward in calls for collective action. In the first case, we see how Martin Luther’s personal struggle with the Roman Catholic monopoly on salvation ignited the Protestant Reformation. The authors then recount how Angelina Grimké and her husband Theodore Dwight Weld, both deeply influenced by populist 19th century evangelicalism, came to see slavery as America’s collective sin and helped lead the radical wing of the abolitionist movement. Finally, one of the lights of the Human Potential Movement of the 1960s and ‘70s, Sister Mary Corita was an artist whose commitment to social justice placed her on the progressive edge of the Catholic Church during the tumultuous days of the Second Vatican Council. Corita advocated for a religious inclusivity that troubled conservatives within the institution, and she paid a high price, eventually leaving her community. But while she was nurtured in the church, she reached beyond it, insisting like the other virtuosi featured here that the pursuit of sanctity could occur outside customary institutional boundaries.

These case studies make for fascinating reading, as do the more limited stories of such figures as Hildegard of Bingen and Steve Jobs. Readers will enjoy learning about all of these exceptional people and their influence on the worlds that both nurtured and opposed them. Given the emphasis on the Reformation as the movement that took holiness outside the cloister to ordinary people, it would be interesting to consider the “Third Orders” that enabled medieval lay people to live the spiritualities of the Carmelites, Franciscans, Dominicans and other orders “in the world”—and still do so today. But Goldman and Pfaff have given us that quintessential sociological gift: the ability to see seemingly private phenomena as social. An intriguing and accessible read, The Spiritual Virtuoso will make an important contribution to scholarship of both religion and social movements.

A small aside: I recently mentioned to Rowan Williams, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, that I was reading this book on spiritual virtuosi. Williams, a celebrated poet and deep contemplative, was enthroned at Canterbury just as the global Anglican Communion threatened to fracture over the ordination of LGBT clergy. I told him the authors pointed out that spiritual virtuosi pay an immense private cost when they assume public roles, and I wondered if that resonated at all? He did eventually speak, but what I most remember is the haunted look on his face. I think Goldman and Pfaff are onto something.

Susan Pitchford is a senior lecturer in the Department of Sociology. She regularly teaches courses on race relations, public education, and comparative social problems. She also leads Study Abroad trips to Rome, where students study early modern Christianity.

*Steve Pfaff is Professor of Sociology at the University of Washington