By now most Americans realize the pandemic revealed deep structures of economic inequality in our society. One tool that tech optimists suggest could solve financial problems for those in need is crowdfunding, using sites like GoFundMe, where individuals create fund-raising campaigns to share on social media. The dream is that each campaign will ‘go viral,’ strangers will be moved to help, and the donations will pour in to fully cover the need of the moment. But graduate student Mark Igra, working in collaboration with Professor Nora Kenworthy (Associate Professor of Nursing and Health Studies at UW Bothell), brought a sociological sensibility to researching crowdfunding of medical costs, and the reality is far less rosy. After publishing several papers on this topic, they conclude that crowdfunding is extremely unlikely to provide an adequate safety net for struggling families or individuals.

The hard truth is that very few campaigns go viral. The vast majority are shared only among the friends and acquaintances of the originator. And herein lies the sociological foundation for Igra and Kenworthy’s research: crowdfunding sites like GoFundMe fundamentally rely on social networks, and networks of real relations tend to link similar people together. Friends often share social traits, live in similar kinds of neighborhoods, and even have roughly similar financial capacity. So crowdfunding campaigns that spread through actual social networks are most likely to reach people who are similarly situated as the one in need.

Writing about Igra and Kenworthy’s research in the New York Times, Shira Ovide summarized it thus, “campaign outcomes reflect the vast inequities in wealth and privilege that lie beneath the veneer of American “opportunity.” In areas with higher levels of education and income, COVID-19 campaigns raised more money. Those areas with higher education and income also produced more campaigns overall — meaning that fewer campaigns were created in the places that needed them most.”

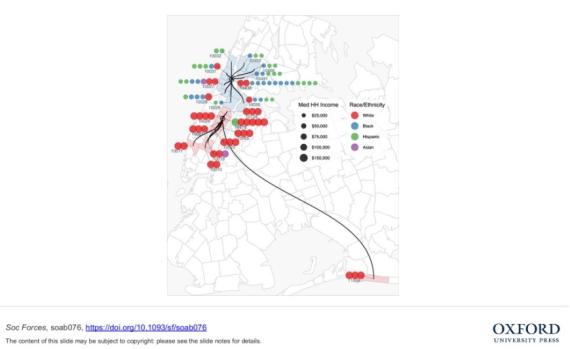

This map highlights the ten zip code tabulation areas most likely to contain Facebook friends for residents of zip codes 10030 (Harlem) and 10075 (Upper East Side) in New York City. The number and expected race and ethnicity of alters shown is based on census population estimates and Facebook friend distributions for networks of equal total size. None of the top twenty-five zip codes for friends is shared between these nearby locations. Donor financial capacity is computed by weighting median incomes by proportion of friends expected across all zip codes

Igra's masters thesis research was the first to directly model the donor side of the process. Analyzing a geographically stratified sample of 2,618 GoFundMe medical campaigns that raters coded for perceived race and ethnicity of the beneficiary, Igra used the geography of Facebook friend networks, the most likely racial and ethnic makeup of the donor pool (based on donor surnames), and census data to estimate the financial capacity of the donor pool for each campaign. While race and geography had no impact on how frequently a campaign was shared, Igra found that the profound racial and geographic stratification in the US explains why campaigns benetting those who live in poorer regions, or those who are Black or Brown, on average raise less money.

As eviction moratoriums and unemployment benefits come to an end, even more people struggle to meet their basic needs. Against this background, some predict the crowdfunding efforts will become more common. But Igra and Kenworthy believe potential donors should be thoughtful about their contributions. Kenworthy suggests, for example, that “if you’re donating to a crowdfunding campaign for a financially stable friend who is being treated for cancer, you could also give to an organization that assists lower-income cancer patients.” Igra adds, “Don’t stop giving to individuals when there are systemic problems but make an effort to think a little more broadly about trying to address the broader issue, not just the individual one.”

Igra’s award-winning masters thesis on geographic and racial variation in the success of campaigns was published in Social Forces, while his co-authored work with Kenworthy on Covid-related campaigns appeared in Social Science & Medicine. This research was featured in the tech section of the New York Times in June and Igra and Kenworthy published an op-ed in the July 20, 2021 edition of the LA Times.